September 2021

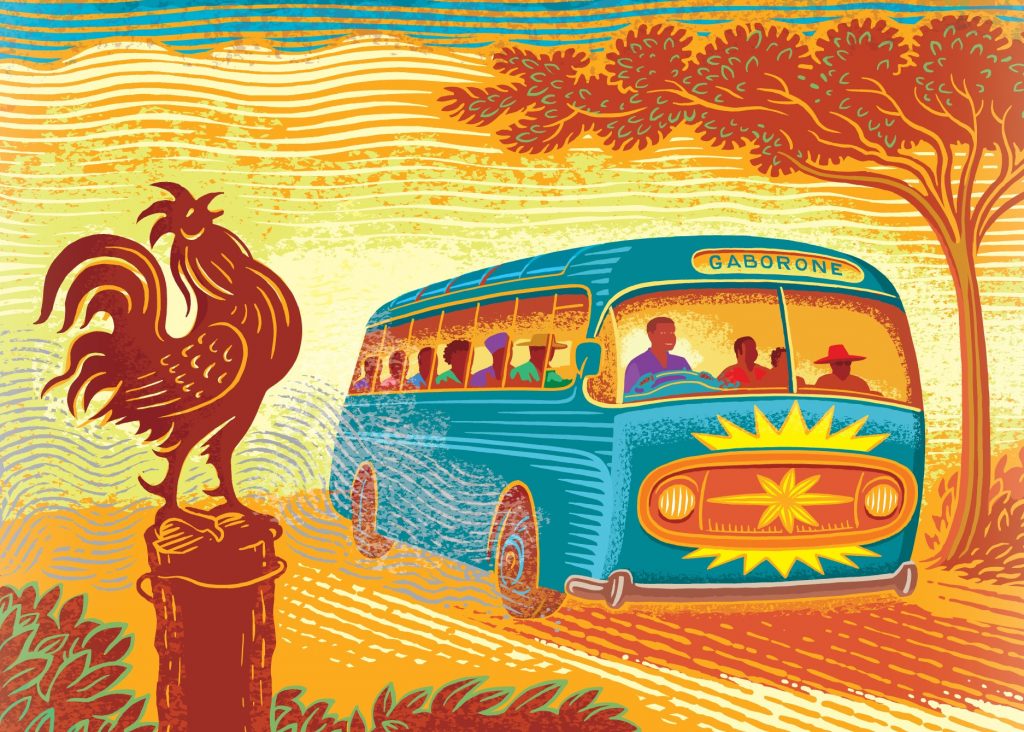

An extract from the first chapter of the latest novel in the No. 1 Ladies’ Detective Agency series, The Joy & Light Bus Company, published in the US & Canada in October.

It was a question to which Mma Ramotswe, like many women in Botswana, and indeed like many women in so many other places, gave more than occasional thought. It was not that she dwelt on it all the time; it was not even that it occupied her mind much of the time, but it was certainly something that she thought about now and then, especially when she was sitting on her veranda in the first light of the morning, looking out at the acacia tree on the other side of the road, in which two Cape doves, long in love, cooed endearments to one another, while for her part she sipped at her first cup of redbush tea, not in any hurry to do whatever it was that she had to do next. That, of course, is always a good time to think – when you know that you are going to have to do something, but you know that you do not have to do it just yet.

The question she occasionally thought about – the question in question, so to speak – was not a particularly complicated one, and could be expressed in a few simple words, namely: how do you keep men happy? Of course, Mma Ramotswe knew that there were those who considered this to be a very old-fashioned question, almost laughable, and there were even those who became markedly indignant at the assumptions that lurked behind such an enquiry. Mma Ramotswe, although a traditional woman in some respects, also considered herself modern in others, and understood very well that women were not placed on this earth simply to look after men. There were unfortunately still men who seemed to hold that view – they had not entirely disappeared – but they were fewer in number, she was happy to observe, and nobody paid much attention to them any longer. These men were called past-tense men by Mma Makutsi, Mma Ramotswe’s friend and colleague – a vivid, if perhaps slightly unkind expression. If any man expressed such sentiments today, Mma Ramotswe reflected, he would have to face phalanxes of angry women challenging him in no uncertain terms. Mma Makutsi would not tolerate attitudes like that, and no man would get away with speaking like that within her earshot. And Mma Makutsi’s hearing, for this and other purposes, was known to be particularly acute.

‘Grace Makutsi can hear an ant walking across the ground,’ Mma Ramotswe had once observed to Mr J. L. B. Matekoni. ‘At least, I am told she can.’

Mr J. L. B. Matekoni had looked incredulous. ‘I do not think so, Mma,’ he said. ‘Ants do not make much noise when they are walking. I think that even other ants do not hear them all that well. I’m not even sure if ants have ears, Mma.’

Mma Ramotswe had smiled. She had not meant her remark to be taken literally, but Mr J. L. B. Matekoni often took things at face value and was not as receptive to metaphor as he might be. This could be owing to the fact that he was a mechanic, and mechanics tended to think in a practical way, or it could just be the way his particular mind worked – it was hard to tell. But even as she smiled at his response, she found herself wondering whether it was true that ants made no noise. She had always imagined that they did – at least when there were enough of them engaged in the sort of joint activity that ants sometimes embarked upon, when they moved in an orderly column, like an army on the march, shifting any blades of dry grass or grains of sand that got in their way. Even tiny ants, acting together in such numbers, could be heard to make a rustling sound, as they went about their unfathomable business. And of course there were enough monuments to that business in those places where termites erected their extraordinary mud towers. Those were astonishing creations – high, tapering piles of hardened mud, red-brown on fresh creation but, when old and weathered, as grey as a long-felled branch or tree-trunk. There must have been some noise in the making of those strange, vertical ant cities, even if there was usually nobody to hear it.

But now she was thinking of that other question – that of how to keep men contented. It was, she thought, a good idea to keep men happy, just as it was a good idea to keep women happy. Both sexes, she thought, might give some thought to the happiness of the other. She knew that there were some women who did not care much about men, and who would not be bothered too much if there were large numbers of discontented men, but she did not think that way herself. Such women, she thought, were every bit as selfish as those men who seemed not to care about the happiness of women. We should all care about each other, she felt, and it made no difference whether an unhappy person was a man or a woman. Any unhappiness, in anybody at all, was a shame. It was as simple as that: it was a shame.

If you were to think about the happiness of men, and if you were to decide that it would be better for any men in your life to be happy rather than unhappy, then what could you do to achieve that goal? One answer, of course, was to say that it was up to men to make themselves happy – that this was not something that women should have to worry about too much, that men should be responsible for themselves. There was some truth in that, Mma Ramotswe thought – men could not expect women to run around after them like nursemaids, but, even then, there were things that women could do to help them to look after themselves and to make their lives a little bit better.

The first thing to do, perhaps, was to look at men and try to work out what it was that men wanted. All of us, Mma Ramotswe thought, wanted something, even if we were unable to tell anybody exactly what it was that we wanted. If you went up to somebody in the street and said, ‘Excuse me, but what is it that you want?’ you might be rewarded with a look of surprise, perhaps even of alarm. But the question was not as odd as it might seem, because there were many people who were not at all sure what they wanted in life, and might do well to ask themselves that unsettling question from time to time.

There were, it was true, some men who looked as if they knew exactly what they wanted. These were the men you saw moving quickly about the place, walking in a purposeful manner, or driving their cars with every indication of wanting to get somewhere as quickly as possible. These were men who were busy, who were going somewhere in order to do something they had already identified as needing to be done. But then there were many men who did not have that air about them. There were many men who just stood about, not going anywhere in particular, or, if they were, not going anywhere with any great appearance of purpose. Were you to ask some of these men what they wanted, they might answer that what they really wanted to do was to sit down. And that, Mma Ramotswe had to admit, was not a bad ambition to have in this life. Many people who were not currently sitting down wanted to do so at some stage in the future – and why not? There was nothing essentially wrong in sitting down and doing nothing in particular. If more people sat down, there would probably be less turmoil in the world – there would certainly be less discomfort.

But there was more to the needs of men than that, thought Mma Ramotswe. At heart, men wanted other people, and in particular women, to like them. Men wanted to be loved. They wanted women to look at them and think, ‘What a nice-looking man that is.’ Even men who were unfortunately not at all nice-looking – and there were men who could do with some improvement in that department – wanted women to think that of them. And they wanted women to think that the things they did were worthwhile, were important, and would not be done if they were not around to do them. Men needed to be needed. That was a simple and easily grasped way of expressing what it was that most men were after, in one way or another.

On that particular day, a day in the hot season before the coming of the rains, Mma Ramotswe happened to have been thinking about these things, and raised the matter with Mma Makutsi as they sat in their office, drinking their mid-afternoon cup of tea, and rather feeling the heat. The conversation had started with a sigh from Mma Makutsi, a way in which she often signalled that she was in a mood to discuss a big and important issue rather than engage in small talk. Small talk had its place, of course – discussion of who had said what about whom, or about what one was going to have for dinner that night, or about what sales were on in what shops – these were all worthy topics of conversation, but had their limits and occasionally made one wish for more substantial conversational fare.

And so it was that after a rather loud and drawn-out sigh from Mma Makutsi’s side of the room, Mma Ramotswe announced, ‘I’ve been thinking, Mma, about what makes men happy.’

Mma Makutsi took a sip of her tea. ‘That is a very big question, Mma, and I am glad that you raised it. I am certainly very glad.’

Mma Ramotswe waited. Mma Makutsi had a way of preceding important observations with a general prologue, rather as a politician might announce a plan to build a new road or excavate a new dam only after making some high-flown remarks on the importance of roads and dams, and about how some political parties are perhaps less aware of this than others. Now, having prepared the ground, Mma Makutsi continued, ‘I have thought of that in the past, and although I wasn’t thinking about it right now, I am certainly prepared to think about it.’

Mma Ramotswe digested this quickly, and went on to say, ‘I know that we women have other things to think about – in some cases we have a list of things as long as your arm.’

Mma Makutsi interrupted her. ‘Oh, that is very true, Mma. If there is any worrying to be done – and there always is – who is doing the worrying? It is the women. We are the ones who do all the worrying. All of it. One hundred per cent. That has always been the case.’

Mma Ramotswe nodded. She was not sure that this was entirely true. She knew a number of men who appeared to shoulder more than their fair share of worrying – that man at the supermarket, for instance, whose job it was to make sure that the tinned food shelves were always fully stocked – he invariably looked worried as he surveyed the aisles of his domain. And one of her near neighbours seemed to be permanently worried, even when she saw him walking his dog in the evening. The dog looked worried too, she thought, although it was sometimes hard to tell with dogs.

She returned to the topic in hand. ‘But we cannot think about ourselves all the time – every so often we should think about men.’

Mma Makutsi weighed this suggestion gravely. ‘That is certainly true, Mma Ramotswe. Women must think about themselves and make sure that they get their fair share of everything . . .’

‘. . . because if they don’t, men will not necessarily give them their due,’ prompted Mma Ramotswe.

It was exactly what Mma Makutsi had been going to say, and she nodded her approval. ‘We women have so much to do,’ she said. And then she sighed again. It was not the sort of sigh that was intended to stop a conversation from proceeding further – it was a sigh that suggested that there were deep issues yet to be plumbed.

‘I suppose one way of looking at it is to think of when it is that men seem to be happiest,’ said Mma Ramotswe. ‘If you can work out when they are happy, then you should know what it is that is making them happy.’

Mma Makutsi looked thoughtful. ‘Phuti Radiphuti always looks happy when he sits down at the table,’ she said. ‘He looks happy when his food is in front of him – particularly if it’s something he likes.’ She paused. ‘And that’s everything, actually, Mma. My Phuti eats everything that is put in front of him.’ She paused again, before adding, ‘Without exception.’ And then adding, further, ‘Except certain things that he does not eat.’

Mma Ramotswe knew from experience that this was true of most men. She knew very few men who were fussy eaters – in fact, she knew none – and it was certainly true of Mr J. L. B. Matekoni that a joint of Botswana beef would produce a look of sublime contentment on his face.

And yet she was uncomfortable about any conclusion that men were concerned only with their stomachs. That was unfair on men, she thought, as most men had other things in which they were interested and that could gladden their spirits. Many men enjoyed football, and were happy talking about it for hours on end. Charlie and Fanwell were a bit like that, and could be found sitting outside the garage at slack times, endlessly discussing the prospects of various football teams. Charlie occasionally demonstrated a tactical point to Fanwell, expertly sending an imaginary ball in the desired direction, watched with admiration by Fanwell, who was not quite as light on his feet as his friend. They were happy at such times, there was no doubt about it, and so that was one thing – football – that lay at the heart of male happiness. And yet there were men who did not take much of an interest in football – Mr J. L. B. Matekoni was one of them – and they must have things that filled the spaces between work and meals. She now asked Mma Makutsi what she thought these things might be, and Mma Makutsi, looking up at the ceiling for inspiration, as she often did, was able to come up with an answer.

‘I think that many men are looking for friends, Mma. Friends are very important to them.’

Mma Ramotswe considered this. It was true, she thought, but then surely it was something that could be said of anybody, man or woman: friends were undoubtedly important. She expressed this view to Mma Makutsi, who agreed, but pointed out that there were special issues when it came to men and their friends.

‘Many men have a big problem with friends, Mma Ramotswe,’ she said. ‘They do not have as many friends as women do. We call this the “male friend deficit”.’

Mma Ramotswe looked at her colleague with interest. She had noticed the way that Mma Makutsi occasionally used the expression ‘we call this’ when expounding on a subject. It was a curious phrase, one of those expressions that seemed to confer additional authority to a statement that was, after all, no more than a personal opinion. By saying ‘we call this’ something or other, Mma Makutsi seemed to be claiming some sort of scientific status for observation, much as a doctor might say to a patient ‘You have what we call . . .’ and then come up with a name that either made the patient feel a whole lot better, or a whole lot worse.

She was not sure where Mma Makutsi had heard about this so-called ‘male friend deficit’; she rather suspected that one might look in vain for it in any textbook, but she had to admit that it sounded impressive. So she said, ‘That is very interesting, Mma. I would like to hear more about it, I think.’

Mma Makutsi raised her tea cup to her lips. ‘It is a big subject,’ she said, and took a sip of tea.

‘You must have read a lot about it, Mma.’

Mma Makutsi nodded. ‘I have read about it in . . .’ She waved a hand airily. ‘In various places. In some books, and in some other places.’

‘In magazines?’

This brought a nod. ‘Yes, in magazines, too. It is something they occasionally talk about in magazines – when they are writing about the problems of men.’

Mma Ramotswe knew that Mma Makutsi subscribed to a number of magazines that she received by post and that were sometimes brought into the office. Left lying on her desk, they were sometimes spotted by Charlie, who would hover over them, squinting at the covers and the indications they gave of the contents within.

‘These magazines have many articles about men,’ he once observed. ‘Look at this one. It says, Inside: special feature on how men think.’ He smiled. ‘So who are these people, Mma Makutsi? Who is writing this stuff that you’re always reading? How do they know how men think, if they are not men themselves? How can they tell what is going on in men’s heads? Have they got special X-ray vision or something?’

Mma Makutsi gave a tolerant smile. ‘These articles are written by experts, Charlie. These people know what they’re talking about – that is why they are called experts.’ She paused. ‘You are not an expert, Charlie.’

This stung. ‘I am not an expert, Mma? You’re saying that I am not an expert?’

‘That is more or less what I am saying, Charlie.’ She paused. ‘I am not saying that you know nothing. That is not what I am saying. You know some things – not many, perhaps, but some. All that I am saying is that there is nothing special on which you can be said to be an expert. That is all.’

Charlie stared at her resentfully. ‘I know a lot about cars,’ he said. ‘And football.’

Mma Makutsi smiled tolerantly. ‘Yes, you may know something about those things, but so does just about every other man. But those are not subjects on which magazines want to publish articles. Do you see any articles entitled What the Zebras should be doing this weekend?’ The Zebras were the main football team in Botswana and the subject of great pride. She answered her own question. ‘Look at any of these magazines and you will not find an article like that. Nor will you find anything about spark plugs or suspension or . . .’ She waved a hand in the air, having exhausted her grasp of mechanical terminology.

Charlie laughed. ‘That is because those magazines you read are for women, Mma. They are not for men.’

‘Then why do you always pick them up and read them when you find them on my desk?’ Mma Makutsi challenged.

Charlie looked sheepish. ‘They have pictures of pretty women in them, Mma. That is why. I do not read the words, but I like to look at the pictures of women.’

‘You see,’ said Mma Makutsi, as if Charlie’s answer somehow proved everything she had said at the beginning of the exchange.

Mma Ramotswe had decided to intervene. ‘I do not think that this discussion is going anywhere,’ she had said, and now she remembered the resentful silence that had followed the termination of the argument. She wished that Mma Makutsi and Charlie would not rub one another up the wrong way – that had been getting better recently, but they still had a tendency to look for areas of disagreement rather than agreement. Perhaps they needed this apparent antipathy: although Mma Ramotswe disliked conflict, she was aware that some people appeared to require what they called creative challenge – what she would call niggling – to keep themselves on their toes.

Now Mma Ramotswe remembered that conversation as she and Mma Makutsi continued with their tea break and considered the interesting question of men and their friends.

‘They are definitely different from us,’ Mma Makutsi ventured. ‘Women have many friends because we look after our friendships.’

Mma Ramotswe nodded. She thought that was true. Women tended their friendships as a gardener might nurture a delicate plant, providing water and shade as required. Men were far more casual about their friends – in general.

‘Let me ask you this, Mma,’ Mma Makutsi began. ‘How many of the men you know do anything about their friends’ birthdays?’

Mma Ramotswe looked up at the ceiling. She tended to do that whenever she had to address a difficult question, although this question was not really difficult. She already knew the answer to this question even before she thought about it: none. She did not know a single man, not one, who marked a friend’s birthday; or even knew when such birthdays were, come to think of it.

‘You see?’ said Mma Makutsi. ‘You see what I mean, Mma? They do not care about these things.’

‘But that does not mean that they don’t care about their friends,’ objected Mma Ramotswe. ‘Maybe it’s just that men think of these things in a different way.’

Mma Makutsi’s rejection of this was adamant. ‘No, Mma, that is not so. Men don’t think about their friends very much. They don’t seem to take much notice of them.’ She paused. ‘In fact, most men couldn’t care less if their friends got up and walked off, Mma.’

She saw the incredulity in Mma Ramotswe’s expression. Mma Makutsi was far too hard on men; far too hard. You could not write off men in quite the way that Mma Makutsi did, thought Mma Ramotswe. Men were a large tribe, and you should not generalise, especially when your generalisations were so dismissive. Men were half the world, after all – although perhaps slightly less than half because they had a lower life expectancy than women, and so there would always be more women than men.

Mma Makutsi shook her finger. ‘No, I mean that, Mma Ramotswe. If their friends got up and walked off, most men would say, “I think my friend has gone.” They would not wonder what had happened. They would not try to find out what their friend was thinking; they would simply say, “I think my friend has gone. That is it. He has gone.” ’

Mma Ramotswe looked doubtful. She would never deny that there were differences between men and women – of course there were – but she had never been comfortable with any suggestion that men were in any way inferior to women. To say that, she felt, was every bit as bad as saying that women were inferior to men, and nobody would stand by and let that be said today. There had been a major change in attitudes – thank heavens – and the idea of equality was now widely accepted, even if there were still some of these past-tense men to whom Mma Makutsi had referred. But even if it had been necessary to expose and challenge the hurtful and false beliefs of the past, it was wrong, she thought, to make belittling remarks about men in general. Mma Makutsi was slightly inclined to do just that, she felt – not all the time, of course, but every so often, and Mma Ramotswe thought that perhaps she herself should be a little bit more forceful in standing up for men – for the good men – who otherwise might be unfairly bundled up with all those past-tense men. There were times when we had to speak out, even if it involved questioning, or even refuting, things said by our friends and colleagues.

She took a deep breath before she spoke. ‘Well, Mma, that’s very interesting,’ she began.

‘Yes,’ said Mma Makutsi, perhaps more firmly than was strictly speaking necessary. ‘It is.’

Mma Ramotswe persisted. ‘I’m not sure if you’re entirely right about men and their friends, Mma.’

The light flashed from Mma Makutsi’s large, round spectacles. This was a warning sign. ‘Oh yes, Mma? Well, I would never say that I am one hundred per cent right about everything – I have never said that, Mma.’

Ninety-seven per cent right, thought Mma Ramotswe, seditiously, doing her very best to prevent herself from smiling.

Mma Makutsi was looking at her, waiting for further elucidation, and so Mma Ramotswe continued, ‘I think that many men are good with their friends. They may not buy them birthday presents, but that does not mean that they have no feelings for them, you know, Mma.’ She paused. ‘Some men like their friends, you know. They like to spend time with them.’ Mma Makutsi took off her spectacles and began to polish them. That, too, was a bad sign, and usually meant that a devastating riposte was about to be made.

‘You may be right, Mma,’ said Mma Makutsi. ‘But let’s just take Mr J. L. B. Matekoni as an example. How many friends does he see in the average week, I wonder? Five? Or maybe a few more? Ten?’

Mma Ramotswe looked up at the ceiling once more. The answer, of course, was, in the average week, none. And yet to give that response would be to suggest that Mr J. L. B. Matekoni had no friends at all, which was simply not true. He was a much-loved man, who was very much appreciated by so many people whom he helped with their cars. Those were his friends. And what about Mma Potokwani? She was his friend, and she often spoke with gratitude about the help he had given the Orphan Farm over the years, fixing its ancient and temperamental water pump and persuading their rattly minibus to continue to operate well after its biblical mileage had been clocked up – twice. When it came to Mr J. L. B. Matekoni’s funeral – and everybody hoped that would not be for a long, long time – then she was sure that the whole country – or at least the whole southern part of the country – would be there. That was the test of how many friends a person had – that was always the real test. And yet, she could not remember when Mr J. L. B. Matekoni had gone to visit a friend, or a friend had come to visit him.

Mma Makutsi sensed Mma Ramotswe’s hesitation. Now her manner changed, and became conciliatory. She liked and admired Mma Ramotswe, and she would never willingly do anything to cause her discomfort.

‘I’m sorry, Mma,’ she said. ‘That is perhaps an unkind question. I know that the answer is probably zero. I am very sorry.’

‘It’s different with men,’ said Mma Ramotswe. ‘They don’t go and have tea with their friends, as we do.’

Mma Makutsi was quick to agree. ‘You’re quite right,’ she said. ‘Men do have friends, Mma, but I think they handle friendship in a different way.’ She paused. ‘And perhaps we should talk about something else.’

Mma Ramotswe took a last sip of her tea. ‘There are many things to talk about,’ she said. But for some reason, neither of them could think of anything, and so the tea break came to an end and they returned to what they had been doing before this awkward, and somewhat unresolved, conversation about men and their friends had begun.

An extract from the first chapter of the latest novel in the No. 1 Ladies’ Detective Agency series, The Joy & Light Bus Company, published in the US & Canada in October.