November 2019

She was twenty-six years old, the daughter of a greengrocer from a town on the Firth of Clyde. Her mother had died when she was twelve – a sudden, acute appendicitis– and her father had brought up her and her younger brother with the help of his unmarried sister, a district nurse. Her brother had taken a job in the shipyards when he was sixteen. “He’s just a boy,” she said. “He’s just a wee boy and there he is with all those men. It’s such a pity.” Her father had sighed. “Pity or not, he’s lucky to have anything these days,” he said. It was 1931.

She was called Margaret, which had been her mother’s name. Her father said that she had grown into the image of her mother. “She was a fine-looking woman,” he said. “Just like you, my darling – just like you.”

She blushed at the compliment. There was no vanity in her; she used make-up, but not very much. “Lilies need no gilding,” said her aunt. “You have good skin. Good skin is one of the greatest gifts, you know, and you don’t need to try to improve it. Remember that.”

The aunt knew all about poverty, and its effects on even the strongest and most determined. She had done her training at the Victoria Infirmary, and then been sent to the Gorbals, where she was attached to a partnership of two doctors, both Highlanders who had spent their working lives in the slums of Glasgow. “You get used to the smell of poverty,” one of the doctors said to her. “After a while, you don’t notice it so much. But it’s always there.” The aunt listened to this, and told her niece that only hard work stood between her and the world of those Gorbals streets. She was very conscious of status and respectability. “People laugh at these things,” she said, “but they wouldn’t if they saw what I saw every day of the week.”

The advice was heeded. Margaret was diligent at school and found a place at a secretarial college in Glasgow. “That’s a good start,” said her aunt. “But she could do even better than that. With her brains – and her looks – she could get somewhere.”

Her father smiled. “She’ll find some nice fellow to marry,” he said. “Or he’ll find her, rather. Somebody who’s made something of himself. Somebody with a good trade – maybe a little business.”

“Possibly,” said the aunt. “They say good looks marry up, don’t they?”

“Perhaps,” said her father, and then added, “Except sometimes.”

“Don’t talk like that,” cautioned the aunt.

After she had finished at the secretarial college she took a job in a bank in Glasgow. She was there for four years, during which she lived as a lodger in a house in the West End. Her aunt approved, as the address was a respectable one. “I think I know the street,” she said. “You’ll like it there.”

The landlady was the widow of a dentist, who had drowned on a fishing trip to the Upper Clyde. The dentist’s widow was kind to her, and full of advice. She chided her gently for not doing more to find a husband. “The best men are taken early,” she said. “Wait too long and you’re left with the alsorans.” Margaret listened politely, but explained that she had no desire to rush things. “I’ll know,” she said. “I’ll know the right man when he comes along. I’m waiting for him, you see.”

“As long as the ship hasn’t already sailed,” replied the widow. “That’s all I’m saying, Margaret.”

The manager of the bank, a thin-faced man with a recalcitrant cough, told her one day that he had heard of a vacancy in a London bank. “This is a very good job,” he said. “One of their top men – and I mean top – is looking for a replacement for the secretary who’s been with him for twenty-seven years. Her eyesight is going and she’s retiring. He needs somebody with the right skills. I know him because he’s married to my cousin. I could put in a word for you, if you like.”

London! But then she wondered where she would live. London was intimidating; you could not just go down to London and find a dentist’s widow with a room to let. She was sure it would not be that simple. The manager, though, had anticipated her concern. “My cousin knows a woman from Glasgow. She lives in a place called Notting Hill and takes lodgers. Well-brought-up girls, of course. Two or three of them, I think. My cousin says she could fix you up there.”

Her father encouraged her. “It’ll be different,” he said. “There’s a lot to do in London, I’m told. I’m not saying that there’s not a lot to do in Glasgow, but London’s bigger, you know. More people. More people means more things to do.”

“There are many opportunities in London,” said her aunt. “But you have to be careful. The English can be lax, you know.”

Margaret took a day or two to decide. Then she told the manager that she would be happy to move; could he have a word with his cousin’s husband? “I already have,” he said. “The job’s yours if you want it.”

She went down to London a month later. The room in Notting Hill was light and clean, with curtains made of thick linen. There was a gas fire that was controlled by a coin-fed meter. A hot bath was available on prior notice to the landlady, who had a measuring stick to ascertain the depth of the water with which it was filled. “Some people think you need to wallow,” she said. “I don’t.”

The job in the bank was more demanding than the position she had filled in Glasgow. Her employer spoke quickly when he dictated letters, and he did not like repeating himself. She worked at improving her shorthand, and after a week she was able to keep up with him without too much difficulty. He was courteous, and appreciative of her work. “You Scots know how to work,” he said.

“We do our best,” said Margaret.

“I can tell that,” he replied.

She wondered about his home life. She knew that he was married, and that he lived in a place called Islington. In order to satisfy her curiosity, she had one Saturday taken a bus to his part of town and found the street on which he lived. She knew the number of his house, and walked past it, but on the other side of the road. She looked up as she drew level with the unremarkable terraced house and saw that he was standing in the window, looking down on the street. She immediately averted her eyes, but she was sure that he saw her. Burning with shame, she hurried down the street.

On the following Monday he asked her how she had enjoyed her weekend. She was flustered, and it took her a few moments to reply. Then she said, “I went for a long walk – all around London – places I had never been to before.” She paused. “Even your part of town, I think.”

He looked at her sideways, obviously uncertain as to how to respond. Then he said, “That’s right – I saw you. Or at least I think I saw somebody who looked a lot like you.”

She affected surprise. “Really?”

“Yes, I thought you walked by my place – on the other side of the street.”

“Possibly. I walked for miles.” She made a show of insouciance. “Probably about fifteen miles altogether. I checked up on a map.”

He smiled at her. “You don’t want to overdo things,” he said.

One afternoon, several months later, she was given time off by her boss. He had to go to a meeting in Manchester and the office was quiet. “You can take the afternoon off,” he said. “You worked late yesterday and you deserve it.”

She left the office shortly after twelve. There was a corner house where she would have lunch – perhaps taking longer over it than she normally would. Then she would go off to Oxford Street to look at the shops. She needed new shoes, and would be able to take her time in finding just the right pair.

The corner house was busy, and she had difficulty finding a table. But then a young man who was already seated indicated that she could take the spare seat opposite him. She thanked him and sat down. She saw that he was gazing at her.

“I’m called Robert,” he said. “Friends call me Bob.”

She told him her name.

“I knew a Margaret once,” he said. “She sang like a nightingale. She really did. A gorgeous voice.”

“I can’t sing,” said Margaret. “I’ve tried, but I can’t. I think you have to train your vocal cords.”

Robert nodded. “Maybe we could go for a walk after lunch,” he said. “Down to the river. It’s such a fine day.”

They walked slowly. Down on the embankment, the sun was on the river, lending it a ripple of gold. Some small boys were throwing stones into the water, shouting out, making the explosive sounds that boys do. A barge was making its stately progress upstream. A ship’s horn sounded.

Margaret looked at Robert – a sideways glance. She liked him, and in a sudden moment of insight she said to herself: this is the man. This is the man I’ve been waiting for. This is the one.

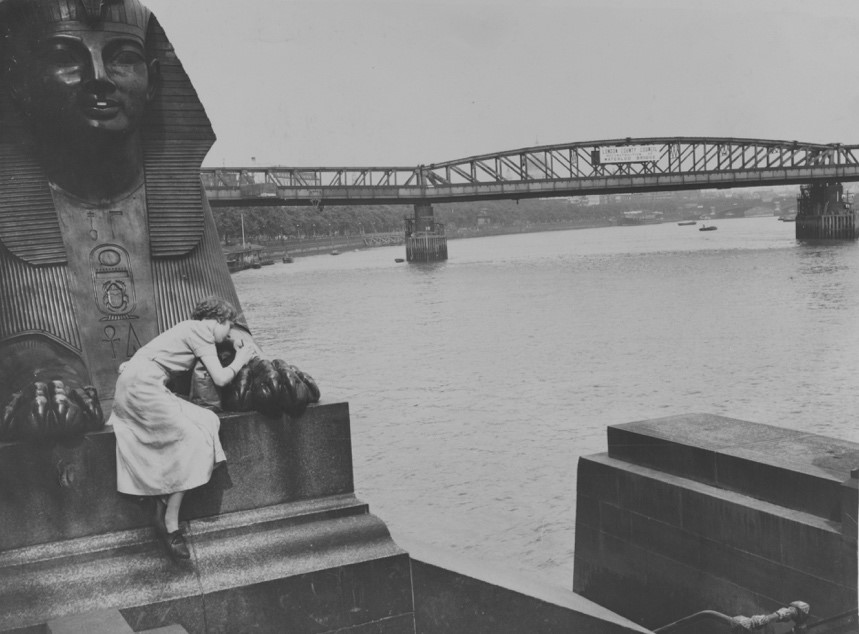

They came to the Needle and the two attendant sphinxes. “I love coming here,” he said. “I’ve always liked the idea of ancient Egypt. Pyramids, sphinxes, what have you. I’ve always loved that sort of thing.”

She gazed up at the sphinx. “You wonder what it’s thinking,” she said. “It looks as if it knows something, but you can’t really tell what it is, can you?”

“That’s how they’re meant to look,” he said. “Enigmatic.”

He paused. “Yes, I come here just about every week. I look at the hieroglyphs and wonder what they mean.”

“Does anybody know?” she asked.

Robert shrugged. “Professors maybe. They know, I think, but the rest of us just have to guess.”

She pointed at the characters. “Maybe that just says: this way round.”

He laughed. “That’s very funny,” he said. “You make me laugh, you know. Oh, in a good way, of course. You’re fun.”

She blushed.

Then he said, “I have to get back to the office. I’m going to be working late tonight, which is why I’ve been able to take this time off. But can you give me your address – I’ll write to you, if you say you don’t mind.”

“I don’t,” she said, hoping that she did not reply too quickly.

She gave him the address in Notting Hill. “You have to write Care of Mrs Higgs. She’s the landlady, and she’s very particular about that sort of thing.”

He wrote down the details in a notebook. “Care of Mrs Higgs,” he said. “Good. That’s it. I’ll send you a postcard and then we can arrange to meet again.”

“I’d like that,” she said, once again worrying that she might sound too eager. The dentist’s widow had advised against that. “Never let them think you’re too keen,” she said. “Men don’t like that. Take my word for it.”

She waited anxiously for his postcard. A week passed, and then another one, and her hopes began to fade. After three weeks she decided that he was not going to write. Mrs Higgs noticed her mood, and asked what was wrong. After hearing the story, the landlady said, “I don’t think you should write him off, you know. He probably lost his notebook. Men lose things all the time, you know.”

That thought preyed on her mind. Eventually she decided that she would go back to the sphinx. He had said that he went there almost every week, and if that were the case she could leave him a message. She would write a note and tuck it between the sphinx’s toes. Her message would be that she thought he might have mislaid her address. If he had, then here it was again and she would love to hear from him – only if he wanted to write, of course.

She left the note in the sphinx’s toes for three Saturdays in a row, replacing it each week because the paper became damp, or washed away. Nothing happened. There was no postcard, no letter. He doesn’t want to see me again, she thought. I should take the hint.

She remembered something her aunt had said to her. “Selfpity, if you ask me, is pitiful. If things go wrong, Margaret– and they will, from time to time – don’t mope. What you need to do is find something else to think about. I know you young people don’t like listening to advice, but that’s the truth, you know. Never indulge in self-pity. Never.”

What, she wondered, would a person keen to avoid selfpity do in her circumstances? She had been disappointed by a meeting with a man. The answer to that, then, was to set about meeting another man. She would go to a dance. She had seen one advertised – a Saturday afternoon dance in a hall not far from where she lived. Refreshments would be served, she read, and music would be by a “rising band, talked about across half London”. She wondered who talked about bands, and why only half London was talking about this one. Why only half London? What about the other half?

She bought a new dress for the occasion and was one of the first people admitted to the dance hall. “You’re keen,” said a woman in the Ladies. “Like me. The early bird catches the worm, they say, don’t they?”

She laughed nervously. “I don’t really know. It’s my first time here.”

The woman smiled. “Don’t worry, dear. You’ll have no trouble. They’ll all want to dance with you – it’s when you get to my age that the field thins out a bit.”

“Are there …” She was not sure how to say it. Surely you shouldn’t talk about men as if they were cattle at a cattle market. But how else could you put it? “Are there plenty of spare fellows?”

The woman clearly found this amusing. “Plenty of spare fellows? Oh, my goodness, all of them are spare. That’s why they come here. It’s how they find a girl. That’s the way it works, you know.” She paused. “This isn’t a church social, you know.”

She did not know how to respond. But her new friend continued. “Mind you, they’re not a bad lot, the men who come here. It’s because you get a good class of man coming here that I choose to patronise the place myself. Men with decent jobs. Respectable men. Men whose fingernails are at least clean.” There was another pause. “Oh, I can tell you about some places where you can’t count on that. You get rough men, you see – the types who have grime under their fingernails. I can’t stand that, you know. Gives me the shudders.”

Margaret said, “I don’t think I’d like that.”

“No. Who would? Anyway, you come in with me and we’ll find a place to sit and listen to the band. The fellows will arrive sure enough – give them time.”

They went into the hall. The hall’s lighting was subdued and the dance floor itself was a pool of darkness in the centre of the room. The band, seated on a dais at the far end of the hall, consisted of half a dozen musicians. A clarinet player, standing up for his solo, was delivering a popular melody. She recognised it, and thought of the words. It was all about heart-strings and how they could be tugged when you were least expecting it. Perhaps it would happen to her today, just as the song said it could. Songs, of course, did not always get it right, but they must be right at least sometimes. People did meet people who inspire them and whom they want to meet again. She had already done that, although she told herself that she should not think about him – that she should not think about sphinxes – especially not when she was trying to meet somebody else.

Her friend was talking about a film she had seen. She was not paying close attention to what was being said, and her mind had drifted when the man came over to speak to her.

“He’s asking you, dear,” whispered the woman.

She stood up, taking the man’s hand as she did so. She let him lead her onto the dance floor, where already a few couples were circling.

He introduced himself. “My name’s Alfred, by the way.”

She gave him her name.

“You don’t like to be called Peggy?”

She shook her head. She had never encouraged that. “And you? Do you like people to call you Alf?”

He looked disapproving. “I think you should stick to the name your parents give you. I feel that quite strongly.”

As they started to dance she looked at him surreptitiously. He wasn’t bad-looking, she thought. In fact, when he turned his head to the side, he was more than that – quite good-looking, she decided. And he was about the right age, too – a bit older than she was, she imagined, but not yet thirty. It was too early, she told herself, to be going out with a man of thirty.

They danced in silence. When the band came to the end of the tune, he thanked her formally and asked her whether she would like some tea and cake.

“They have a very nice sponge cake here, you know. Very fine.”

She wondered how he knew. He must come here regularly to have formed a view on the cake they served.

“I’d love a cup of tea,” she said. “Dancing makes you thirsty, I think.”

He considered this, seeming to weigh the observation as if it were of some profundity. At length he delivered his verdict. “Some dancing does that,” he said. “On the other hand, you can feel quite hot just sitting down. It’s the lights, I think. They generate heat.”

She looked up at the lights. They were bright, at least round the edge of the room, but she could not think of anything much to say about them.

“We had a power cut the other day,” Alfred suddenly remarked. “We were sitting in the front room listening to the Light Programme on the wireless, and suddenly everything went dark.”

“You must have been worried,” she said.

He considered this too. “Maybe. A bit. But then, when the lights go out suddenly like that, you realise that it’s probably a power cut. That’s what I thought, anyway.”

“Oh.”

“Yes. And my mother was in the room too. She was listening to the wireless with me and of course the BBC went off the air. Just silence.”

“I suppose, with the power going off …”

“Yes,” he agreed. “The wireless couldn’t work without electricity. But then, you know what my mother said? She said: you’d think the lights wouldn’t go off while you’re listening to the Light Programme. The Light Programme, you see – a different sort of light, of course.”

She laughed dutifully, but she found herself looking towards the door. It was too early to make an excuse, but she would do so, in twenty minutes, perhaps – after they had drunk their tea and eaten the sponge cake. Twenty minutes could be endured.

He went to fetch the tea. While he was away, she saw the woman she had met in the Ladies. She was on the dance floor now, in the arms of a tall man with slicked-back hair and protruding teeth. She caught Margaret’s eye and waved; Margaret thought she winked, but could not be sure.

Alfred put the cup of tea in front of her.

“Don’t let it get cold,” he warned. “There’s nothing worse than cold tea.”

She wanted to say, “Oh, but there are plenty of things far worse.” But she simply smiled and raised the cup to her lips.

“If you’re wondering what I do,” he said, “I’m a road engineer. I work in the office most of the time – deciding which roads we’ll repair next. You won’t find me out on the streets – looking into a ditch or anything like that.”

She realised that this was a joke, and she laughed. “You don’t operate one of those signs that says Go, do you?”

“Oh, heavens no. We have Irishmen to do that. That’s Paddy’s job.”

“Are they all Irish?” she asked.

“Oh yes. Most of them. Nice fellows, for the most part. Except when they get involved in a fight. You have to be careful then. They take their fights seriously. And horses too. They love their horses, the Irish.”

“I suppose they’re just people, like the rest of us.”

He frowned. “To a certain extent,” he said.

Suddenly she asked him, “Would you ever like to visit the pyramids?”

He looked puzzled. “No, not really. It’s very hot out there.”

“In Egypt?”

“Yes. They’re on the edge of the desert, aren’t they? I don’t like the thought of that. Or the flies. Egypt has lots of flies, I’m told. The pyramids are probably crawling with them.”

She looked at her watch. And then, impulsively, she blurted out, “Oh no! I’ve forgotten. It’s Mrs Higgs’ birthday and I was going to get her flowers.”

He asked who Mrs Higgs was.

“My landlady. She’s been very good to me. Her daughter told me that today was her birthday and I wanted to surprise her.” She looked at her watch again. “I hope you don’t mind. I really need to go.”

He shook his head. “I don’t mind at all,” he said. “In fact, I’m not all that keen on the band. I’ll come and help you get the flowers. Do you mind?”

She hesitated, and then replied, “No. That’s kind of you.”

They bought the flowers – a large bunch of red and white carnations. He said, “I’ll see you home safely,” as they left the florist.

“It’s really not necessary.” She was wondering what she would do with the flowers. The birthday was a lie – a pretext – and she was not sure where she would find a vase for the flowers. Perhaps she could give them to Mrs Higgs anyway, as a general thank-you present for being a thoughtful landlady.

“I’d like to,” he said. “You shouldn’t wander about London too much on your own. Not these days.”

“It’s not all that late.”

He brushed aside her objections. “There are always undesirables. Always.”

She wondered whether, being a road engineer, he was privy to information she did not have; perhaps road engineers knew where the undesirables were.

She was firm at the door of the house. “I must say goodnight here,” she said. “Mrs Higgs doesn’t permit visitors.”

“No,” he said. “Very wise.”

“So, goodnight, Alfred. And thank you … for the tea and cake.”

“It was my pleasure.”

She waited for him to go.

“Would you come to tea with me and my mother?” he asked. “She’d love to meet you. I know she would.” He paused. “She has albums of photographs of her trips to France. She’s been five times. She speaks a bit of French, you see.”

She closed her eyes. She should say no; she should make it clear. But instead she said, “That would be very kind.”

“Next Saturday?”

She suppressed a sigh. “Yes. Next Saturday.”

His mother was called Annette. She wore her hair in a bun.

“I don’t speak a lot of French,” she said. “I learned it at school, of course, as we all did, but school French is so different, isn’t it? All this business about la plume de ma tante. Whoever imagined that an aunt’s pen might be found in the garden?”

Margaret shook her head. “I have no idea.”

“No, nor do I. I found, though, that if I talked to people – actually talked to them – I learned a lot. And the French don’t mind talking French, you know – in fact, they like to talk French, I find.”

The conversation continued. The photograph albums were produced and discussed. Alfred said very little, and when he went out of the room to put the kettle back on, Annette leaned towards Margaret and whispered, “He’s a lovely boy, you know. He lacks confidence – that’s all.”

She did not know what to say.

Then Annette continued. “Don’t rush him. Let him take things at his own speed.”

She opened her mouth to speak. But Annette continued,

“He’ll treat you well, my dear. His father was a real gentleman. He was an engineer too – a different sort, though. He was mainly bridges. Alfred picked things up from him, though. That’s where the engineering came from. There’s always an explanation for everything. We don’t become what we become by accident.”

She asked how her interest in France had arisen. Annette thought for a moment. “I heard somebody speaking French,” she said. “And I thought: I’d like to be able to do that. That’s how it happened, I think. Amazing.”

Three months later, Alfred said to her, “How long have we been seeing one another?”

She shrugged. “A few months.”

“Yes,” he said. “A few months.”

She waited. She had decided that she would have to tell him. It was unfair of her to continue to let him think that this would develop into something. She had accepted his invitations only because she had had nothing else to do and she felt sorry for him. He was lonely – and she was lonely too; there was no harm in going to the dance hall together or the cinema. And in the cinema it was hard to push him away from her, and she had succumbed to the hand-holding that he seemed to like. They held hands throughout the film and it made their palms hot and sticky – not that he seemed to

mind.

And now here he was about to say something that would put her in a spot. She would have to speak.

“I think I’m going to go back to Glasgow,” she said, adding, “next week.”

He stared at her in dismay. “Glasgow?” he stuttered.

She nodded. “My aunt is unwell. She needs me to look after her.”

It was pure invention, and she felt a momentary pang: you should not lie about people’s health, she thought. You bring about the thing you invent. That was the danger.

He seemed reassured. “Oh, just until she’s better …”

“Which won’t be for a long time,” she said. “My aunt’s very ill.”

“I’m sorry. What is it? Do you mind my asking?”

She looked at the floor. “I’d prefer not to talk about it.”

“It isn’t polio, is it?”

She shook her head. “It’s her chest.”

“TB?”

“I said, I’d prefer not to talk about it.” She closed her eyes. “Her heart, actually. Her heart is enlarged.”

“Oh …”

“Yes. It’s all swollen up.”

“I’m sorry.”

“So I have to go, Alfred.”

He looked anguished. “As it happened, I was going to say…”

“No,” she said. “It’s best not to talk about it.”

That would have been her opportunity to end it, but the following day she sent him a postcard to tell him that her aunt had made a dramatic recovery. She had felt guilty over the lie. She thought: you have to take the person you are allocated in his life. She had been given Alfred, and she should accept it. There were plenty of much duller men in London – she had met a number of them – and he would be solid and reliable. She could do far worse.

He told her how delighted he was that she would not be returning to Glasgow. “I’d like to take you out to dinner,” he said. “Not just an ordinary meal. I’d like to go somewhere special. We could make it a special occasion.”

She knew immediately what he meant, and that this, rather than the dinner itself, was the moment of decision. He would ask her to marry him. She had allowed this situation to develop. She had drifted into something, in the way in which we are all capable of drifting into things, without any

conscious assertion of will, any firm choice, because it is easy and we feel sorry for people and we cannot find a simple way of avoiding their emotional claims. She should have found an excuse not to go out to dinner, but she did not, because her drift had continued, and now it was too late.

I have one last afternoon, she thought. I have one last afternoon as myself before I become an engaged woman. She went for a walk, almost in a daze, conscious that her future was approaching her like a car on a dark road, and she was caught in its headlights. She walked through Bedford Square. She stopped to talk to a woman selling flowers, who gave her some sort of blessing she could not understand, but in which the words good luck stood out. She stopped to help a child who had tripped and grazed his knees. She gave him her handkerchief to wipe away the tiny lines of blood. He looked up at her and smiled, and she used the handkerchief to attend to his streaming nose. And then, a short distance away, behind the glass of a noticeboard, she saw the announcement of an exhibition of Egyptian artefacts. This was in the British Museum, and it was free. She hesitated, and then went in. He loved ancient Egypt – he had told her that.

She saw him standing next to a roll of papyrus. An ancient clerk had covered the papyrus with hieroglyphs. Her heart beating loudly within her, she approached him.

He turned and saw her. She had half-expected his face to fall, as it can do when we encounter somebody we hoped to avoid. But this did not happen. He smiled broadly, and reached out for her hand. He said he could not believe it. He had been distraught at the loss of the notebook in which he had noted her address. How does one find a lost person in London? It was impossible.

“Have you been down to the Sphinx?” she asked.

He looked puzzled. “No, I’ve been a bit busy.”

He pointed to the papyrus. “Look at that,” he said. “Think how old that is.”

She stared at the faint text.

“What does it say?” she asked.

He looked down. “It says: I love you very much.”

“Really?”

“Yes, and then it says, I am glad we have found one another.”

She bent down to examine the symbols more closely. Somebody had written these all those years ago; somebody had actually touched this paper all those years ago.

“Does it really say that?” she asked. “Does it really?”

He smiled. “No,” he said. “That’s me talking.”

________________________________________

This story is published as part of a new book called Pianos & Flowers: Brief Encounters of the Romantic Kind, a collection of short stories inspired by photographs from the Sunday Times archive. It is published in the UK on the 7th November by Polygon.