Welcome to Scotland Street, a quiet urban neighbourhood in the author's home town of Edinburgh where the inhabitants lead extraordinary lives and little Bertie Pollock is at the centre of it all.

Alexander McCall Smith’s 44 Scotland Street series is the world’s longest running serial novel. Readers all over the world delight in his amusing characters and descriptions of the city of Edinburgh.

With The 44 Scotland Street Cookbook fans can now immerse themselves in the world of Edinburgh’s New Town and eat like their favourite characters. Anna Marshall has ransacked the pages (and cupboards!) of 44 Scotland Street to find all the best snacks, treats and dinners enjoyed by its inhabitants.

Step into the world of Edinburgh foodies and enjoy Big Lou’s ‘Off the Record’ Bacon Rolls, Bertie’s much-loved Panforte di Sienna or Angus Lordie’s famous cheese scones.

‘I hope that this work will strengthen the friendship that readers of the Scotland Street series have with the inhabitants of that address. I am most grateful to Anna for writing this cookbook. She has helped to make the world of Bertie, Big Lou, Domenica and all the others come to life. They are inviting you in. The table is laid. Please join them.’ – Alexander McCall Smith

About the author: Anna Marshall is an arts administrator, events organiser, publicist and fundraiser. She has been working with Alexander McCall Smith for 13 years, giving her an intimate knowledge of the 44 Scotland Street series. She lives on a farm in the Scottish Borders, farming sheep and cows and publishing recipes on the farm’s website.

The Enigma of Garlic – the latest installment in the charming and congenial 44 Scotland Street series finds all our favorite residents of Scotland’s most celebrated address up to their usual hilarious hijinks.

It’s the most anticipated event of the decade – Big Lou and Fat Bob’s wedding – and everyone is invited! But the relative peace and tranquillity of 44 Scotland Street is about to be disrupted. Domineering Irene is set to return for a two-month stay, consigning young Bertie to a summer camp. Not content with that, she somehow manages to come between the enigmatic nun, Sister Maria-Fiore dei Fiori di Montagna, and her friend, the hagiographer, Antonia Collie. And can a person really change, even after being struck by lightning? Bruce Anderson’s metamorphosis and new-found outlook on life is put to the test as he prepares to leave his creature comforts for the monastic simplicity of Pluscarden Abbey. His house sitter, meanwhile, gets a little too comfortable in his new life and discovers that his talented employer’s shoes are all too easy to slip into. With great taste comes great responsibility.

Alexander McCall Smith’s delightfully witty, wise and sometimes surreal comedy spirals out in surprising ways in this new installment, but its heart remains where it has always been, at the center of life in Edinburgh’s New Town.

Read more about your favourite Scotland Street characters here.

Reviews

Welcome to No. 44 Scotland Street, a fictitious building in a real street in Edinburgh. Follow the characters as they struggle with the moral dilemmas of everyday life.

In the first of this delightful series, Pat Macgregor moves in to 44 Scotland Street with the narcissistic Bruce Anderson. Bruce, an Edinburgh chartered surveyor and stalwart of the Conservative Association, dreams of membership of Scotland’s most exclusive golf club. Their neighbours include Irene Pollock, the pushy Stockbridge mother, and her prodigiously talented five-year old son Bertie, who is making good progress with the saxophone and with his Italian. And last but not least there is Domenica Macdonald, that type of Edinburgh lady who sees herself as a citizen of a broader intellectual world.

44 Scotland Street is vintage McCall Smith. The series tackles trust and honesty, snobbery and hypocrisy, love and loss with the lightest of touch. Clever, elegant and funny, these novels provide huge entertainment.

Reviews

Excerpt

It was settled. Pat had agreed to move in, and would pay rent from the following Monday. The room was not cheap, in spite of the musty smell (which Bruce pointed out was temporary) and the general dinginess of the décor (which Bruce had ignored). After all, as he pointed out to Pat, she was staying in the New Town, and the New Town was expensive whether you lived in a basement in East Claremont Street (barely New Town, Bruce said) or in a drawing-room flat in Heriot Row. And he should know, he said. He was a surveyor.

“You have found a job, haven’t you?” he asked tentatively. “The rent ... ”

She assured him that she would pay in advance, and he relaxed. Anna had left rent unpaid and he and the rest of them had been obliged to make up the shortfall. But it was worth it to get rid of her, he thought.

He showed Pat to the door and gave her a key. “For you. Now you can bring your things over any time.” He paused. “I think you’re going to like this place.”

Pat smiled, and she continued to smile as she made her way down the stair. After the disaster of last year, staying put was exactly what she wanted. And Bruce seemed fine. In fact, he reminded her of a cousin who had also been keen on rugby and who used to take her to pubs on international nights with all his friends, who sang raucously and kissed her beerily on the cheek. Men like that were very unthreatening; they tended not to be moody, or brood, or make emotional demands—they just were. Not that she ever envisaged herself becoming emotionally involved with one of them. Her man—when she found him—would be ...

“Very distressing! Very, very distressing!”

Pat looked up. She had reached the bottom of the stair and had opened the front door to find a middle-aged woman standing before her, rummaging through a voluminous handbag.

“It’s very distressing,” continued the woman, looking at Pat over half-moon spectacles. “This is the second time this month that I have come out without my outside key. There are two keys, you see. One to the flat and one to the outside door. And if I come out without my outside key, then I have to disturb one of the other residents to let me in, and I don’t like doing that. That’s why I’m so pleased to see you.”

“Well-timed,” said Pat, moving to let the woman in.

“Oh yes. But Bruce will usually let me in, or one of his friends ... ” She paused. “Are you one of Bruce’s friends?”

“I’ve just met him.”

The woman nodded. “One never knows. He has so many girlfriends that I lose track of them. Just when I’ve got used to one, a quite different girl turns up. Some men are like that, you know.”

Pat said nothing. Perhaps wholesome, the word which she had previously alighted upon to describe Bruce, was not the right choice.

Having lost his job as a chartered surveyor, Bruce, the intolerably vain and perpetually deluded ex-surveyor, is about to embark on a new career as a wine merchant. His long-suffering flatmate Pat Macgregor, set up by matchmaking Domenica Macdonald, finds herself invited to a nudist picnic in Moray Place.

Six-year old Bertie Pollock plots rebellion against his bossy, crusading mother Irene and his psychotherapist Dr Fairbairn. But when Bertie’s longed-for trip to Glasgow with his ineffectual father Stuart ends up with Bertie taking money from legendary Glasgow hard man Lard O’Connor at cards, it looks as though the lad should have been more careful what he wished for.

Reviews

Excerpt

Pat saw nothing in her father’s face of the hollow dread he felt. He was accomplished at concealing his feelings, of course, as all psychiatrists must be. He had heard such a range of human confessions that very little would cause him so much as to raise an eyebrow or to betray, with so much as a transitory frown, disapproval over what people did, or thought, or perhaps thought about doing. And even now, as he sat like a convicted man awaiting his sentence, he showed nothing of his emotion.

“Yes,” said Pat. “I’ve written to St Andrews and told them that I don’t want the place next month. They’ve said that’s fine.”

“Fine,” echoed Dr Macgregor faintly. But how could it be fine? How could she turn down the offer from that marvellous place, with all that fun and all that student nonsense, and Raisin Week and Kate Kennedy and all those things? To turn that down before one had even sampled it was surely to turn your back on happiness.

“I’ve decided to go to Edinburgh University instead,” went on Pat. “I’ve been in touch with the people in George Square and they say I can transfer my St Andrews place to them. So that’s what I’m going to do. Philosophy and English.”

For a moment Dr Macgregor said nothing. He looked down at his shoes and saw, as if for the first time, the pattern of the brogue. And then he looked up and glanced at his daughter, who was watching him, as if waiting for his reaction.

“You’re not cross with me, are you?” said Pat. “I know I’ve messed you around with the two gap years and now this change of plans. You aren’t cross with me?”

He reached out and placed his hand briefly on hers, and then moved his hand back.

“Cross is the last thing I am,” he said, and then burst out laughing. “Does that sound odd to you? Rather like the word order of a German or Yiddish speaker speaking English? They say things like, ‘Happy I’m not,’ don’t they? Remember the Katzenjammer Kids?”

Of course she didn’t. Nor did she know about Max und Moritz nor Dagwood and Blondie, he suspected—those strange denizens of that curious nowhere world of the cartoon strips—although she did know about Oor Wullie and the Broons. Where exactly was that world, he wondered? Dundee and Glasgow respectively, perhaps, but not exactly.

Pat smiled. “I’m glad,” she said. “I just decided that I’m enjoying myself so much in Edinburgh that I should stay. Moving to St Andrews seemed to me to be an interruption in my life. I’ve got friends here now ... ”

“And friends are so important,” interrupted her father, trying to think of which friends she had in mind, and trying all the time to control his wild, exuberant joy. There were school friends, of course; the people she had been with at the Academy during the last two years of her high school education. He knew that she kept in touch with them, but were those particular friendships strong enough to keep her in Edinburgh? Many of them had themselves gone off to university elsewhere, to Cambridge in one or two cases, or to Aberdeen or Glasgow. Was there a boy, perhaps? There was that young man in the flat in Scotland Street, Bruce Anderson; she had obviously been keen on him but had thought better of it. What about Matthew, for whom she worked at the gallery? Was he the attraction? He might speculate, but any results of his speculation would not matter in the slightest. The important thing was that she was not going to Australia.

Back to Scotland Street we go, and six-year old Bertie is still battling against his insufferable mother and her psychotherapist crony Dr Fairbairn, making a short-lived bid for freedom on a trip to Paris with the Edinburgh Youth Orchestra. Domenica sets off on an anthropological odyssey with pirates in the Malacca Straits, while Pat attracts several handsome admirers, including a toothsome suitor named Wolf. Meanwhile Big Lou, eternal source of coffee and good advice to her friends, has love, heartbreak and erstwhile boyfriend Eddie’s misdemeanours on her own mind.

Reviews

Excerpt

At the end of the seminar, when Dr Fantouse had shuffled off in what can only have been disappointment and defeat, back to the Quattrocento, the students snapped shut their notebooks, yawned, scratched their heads, and made their way out of the seminar room and into the corridor. Pat had deliberately avoided looking at Wolf, but she was aware of the fact that he was slow in leaving the seminar room, having dropped something on the floor, and was busy searching for it. There was a noticeboard directly outside the door, and she stopped at this, looking at the untidy collection of posters which had been pinned up by a variety of student clubs and societies. None of these was of real interest to her. She did not wish to take up gliding and had only a passing interest in salsa classes. Nor was she interested in teaching at an American summer camp, for which no experience was necessary, although enthusiasm was helpful. But at least these notices gave her an excuse to wait until Wolf came out, which he did a few moments later.

She stood quite still, peering at the small print on the summer camp poster. There was something about an orientation weekend and insurance, and then a deposit would be necessary unless ...

“Not a nice way to spend the summer,” a voice behind her said. “Hundreds of brats. No time off. Real torture.”

She turned round, affecting surprise. “Yes,” she said. “I wasn’t really thinking of doing it.”

“I had a friend who did it once,” said Wolf. “He ran away. He actually physically ran away to New York after two weeks.” He looked at his watch and then nodded in the direction of the door at the end of the corridor. “Are you hungry?”

Pat was not, but said that she was. “Ravenous.”

“We could go up to the Elephant House,” Wolf said, glancing at his watch. “We could have coffee and a sandwich.”

They walked through George Square and across the wide space in front of the McEwan Hall. In one corner, their skateboards at their feet, a group of teenage boys huddled against the world, caps worn backwards, baggy, low-crotched trousers half-way down their flanks. Pat had wondered what these youths talked about and had concluded that they talked about nothing, because to talk was uncool. Perhaps Domenica could do field work outside the McEwan Hall—once she had finished with her Malacca Straits pirates—living with the skateboarders, in a little tent in the rhododendrons at the edge of the square, observing the socio-dynamics of the group, the leadership struggles, the badges of status. Would they accept her, she wondered? Or would she be viewed with suspicion, as an unwanted visitor from the adult world, the world of speech?

She found out a little bit more about Wolf as they made their way to the Elephant House. As they crossed the road at Napier’s Health Food Shop, Wolf told her that his mother was an enthusiast of vitamins and homeopathic medicine. He had been fed on vitamins as a boy and had been taken to a homeopathic doctor, who gave him small doses of carefully chosen poison. The whole family took Echinacea against colds, regularly, although they still got them.

“It keeps her happy,” he said. “You know how mothers are. And it’s cool by me if my mother’s unstressed. You know what I mean?”

Pat thought she did. “That’s cool,” she said.

And then he told her that he came from Aberdeen. His father, he said, was in the oil business. He had a company which supplied valves for off-shore wells. They sold valves all over the world, and his father was often away in places like Houston and Brunei. He collected air miles which he gave to Wolf.

“I can go anywhere I want,” he said. “I could go to South America, if I wanted. Tomorrow. All on air miles.”

“I haven’t got any air miles,” said Pat.

“None at all?”

“No.”

Wolf shrugged. “No big deal,” he said. “You don’t really need them.”

“Do you think that Dr Fantouse has any air miles?” asked Pat suddenly.

They both laughed. “Definitely not,” said Wolf. “Poor guy. Bus miles maybe.”

Poor put-upon Bertie is still struggling to escape his overbearing mother’s influence, his yoga lessons, and his pink bedroom, while wondering why new baby brother Ulysses looks uncomfortably like his psychotherapist. Bruce has returned from London to land, on his feet and rent-free, in the arms of heiress Julia Donald.

But all is not well among the residents of 44 Scotland Street: painter Angus’s dog Cyril is under threat of execution, while Pat and hopeless romantic Matthew are on the verge of making the most terrible mistake of their lives.

Can they rescue things from the brink? Or will the residents of 44 Scotland Street descend into chaos?

Reviews

Excerpt

“Chinos,” she said suddenly.

Matthew looked up, clearly puzzled. “Chinos?”

“Yes,” said Pat. “Those trousers they call chinos. They’re made of some sort of thick, twill material. You know the sort?”

Matthew thought for a moment. He glanced down at his crushed-strawberry corduroy trousers; he knew his trousers were controversial—he had always had controversial trousers, but he rather liked this pair and he had seen a lot of people recently wearing trousers like them in Dundas Street. Should he have been wearing chinos? Was this Pat’s way of telling him that she would prefer it if he had different trousers?

“I know what chinos are,” he said. “I saw a pair of chinos in a shop once. They were ... ” He tailed off. He had rather liked the chinos, he remembered, but he was not sure whether he should say so to Pat: there might be something deeply unfashionable about chinos which he did not yet know.

“Why are they called chinos?” Pat asked.

Matthew shrugged. “I have no idea,” he said. “I just haven’t really thought about it ... until now.” He paused. “But why were you thinking of chinos?”

Pat hesitated. “I just saw a pair,” she said. “And ... and of course Bruce used to wear them. Remember?”

Matthew had not liked Bruce, although he had tolerated his company on occasion in the Cumberland Bar. Matthew was a modest person, and Bruce’s constant bragging had annoyed him. But he had also felt jealous of the way in which Bruce could capture Pat’s attention, even if it had become clear that she had eventually seen through him.

“Yes. He did wear them, didn’t he? Along with that stupid rugby jersey. He was such a ... ” He did not complete the sentence. There was really no word which was capable of capturing just the right mixture of egoism, hair gel and preening self-satisfaction that made up Bruce’s personality.

Pat moved away from Matthew’s desk and gazed out of the window. “I think that I just saw Bruce,” she said. “I think he might be back.”

Matthew rose from his desk and joined her at the window. ‘Now?’ he said. ‘Out there?”

Pat shook her head. “No,” she said. “Further up. I was on the bus and I saw him—I’m pretty sure I did.”

Matthew sniffed. “What was he doing?”

“Walking,” said Pat. “Wearing chinos and a rugby jersey. Just walking.”

“Well, I don’t care,” said Matthew. “He can come back if he likes. Makes no difference to me. He’s such a ... ” Again Matthew failed to find a word. He looked at Pat. There was something odd about her manner; it was as if she was thinking about something, and this raised a sudden presentiment in Matthew. What if Pat were to fall for Bruce again? Such things happened; people encountered one another after a long absence and fell right back in love. It was precisely the sort of thing that novelists liked to write about; there was something heroic, something of the epic, in doing a thing like that. And if she fell back in love with Bruce, then she would fall out of love with me, thought Matthew; if she ever loved me, that is.

To the casual observer, the great enlightened city of Edinburgh, home of no-nonsense philosophers and cream teas, might appear immune to the rollercoaster of strong emotions. But at 44 Scotland Street, as Matthew and Elspeth embark on the risky enterprise of married love, the raffish portrait painter Angus Lordie has a premonition of disaster. Soon enough Irene Pollock is shocked to learn that her small son Bertie has a highly unsuitable ambition; the gloriously vain Bruce discovers a wrinkle and confronts rejection; and Angus finds himself facing the grave consequences of unbridled bliss, not to mention a large Glaswegian gangster bearing gifts.

Reviews

Excerpt

The wedding took place underneath the Castle, beneath that towering, formidable rock, in a quiet church that was reached from King’s Stables Road. Matthew and Elspeth Harmony had made their way there together, in a marked departure from the normal routine in which the groom arrives first, to be followed by the bride, but only after a carefully timed delay, enough to make the more anxious members of her family look furtively at their watches—and wonder.

Customs exist to be departed from, declared Matthew. He had pointedly declined to have a stag party with his friends but had none the less asked to be included in the hen party that had been organised for Elspeth.

“Stag parties are dreadful,” he pronounced. “Everybody has too much to drink and the groom is subjected to all sorts of insults. Left without his trousers by the side of the canal and so on. I’ve seen it.”

“Not always,” said Elspeth. “But it’s up to you, Matthew.”

She was pleased that he was revealing himself not to be the type to enjoy a raucous male-only party. But this did not mean that Matthew should be allowed to come to her hen party, which was to consist of a dinner at Howie’s restaurant in Bruntsfield, a sober do by comparison with the Bacchanalian scenes which some groups of young women seemed to go in for. No, new men might be new men, but they were still men, trapped in that role by simple biology.

“I’m sorry, Matthew,” she said. “I don’t think that it’s a good idea at all. The whole point about a hen party is that it’s just for women. If a man were there it would change everything. The conversation would be different, for a start.”

Matthew wondered what it was that women talked about on such occasions. “Different in what way?” He did not intend to sound peevish, but he did.

“Just different,” said Elspeth airily. She looked at him with curiosity. “You do realise, Matthew, that men and women talk about rather different things? You do realise that, don’t you?”

Matthew thought of the conversations he had with his male friends. “I don’t know if there’s all that much difference,” he said. “I talk about the same things with my male and female friends. I don’t make a distinction.”

“Well, I’m sorry,” said Elspeth. “But the presence of a man would somehow interrupt the current. It’s hard to say why, but it would.”

So the subject had been left there and Elspeth in due course enjoyed her hen party with seven of her close female friends, while Matthew went off by himself to the Cumberland Bar.

The extended family of 44 Scotland Street is trembling on the brink of reckless self-indulgence. Matthew and Elspeth receive startling news on a visit to the Infirmary. Angus and Domenica are contemplating an Italian ménage a trois, and even Big Lou is overheard discussing cosmetic surgery. But when Bertie Pollock, six years old and impatient to be seven, loses his meddling mother Irene one afternoon, it becomes clear that wish fulfilment is a dangerous business.

Warm-hearted, wise and very funny, The Importance of Being Seven brings us a fresh and delightful set of insights into philosophy and fraternity among Edinburgh’s most loveable residents.

Reviews

Excerpt

For Matthew and his wife, Elspeth Harmony, the adjustment to married life was both rapid and thoroughly pleasant. Neither had the slightest doubt that the right choice had been made—not only in respect of deciding to get married at all, but also in their choice of partner. Matthew loved Elspeth Harmony—he loved her to the extent that everything that was associated with her, her possessions, her sayings, her friends and connections, were all endowed with a quality of specialness that attached to nothing else. The mug from which she drank her morning coffee was special because her lips had touched it; the tortoiseshell comb that she kept on top of the dressing table was special because it had belonged to Elspeth’s grandmother rather than to any other grandmother; the shopping list that she wrote out to take with her to Valvona & Crolla was special because it was in her handwriting. His affection for her was total, and touching.

For her part, Elspeth could not believe the sheer good fortune that had brought them together. She had always wanted to get married, from her university days onwards, but as the years passed—and she was only twenty-eight at the time of Matthew’s proposal—she had become increasingly concerned that nobody would ask her. There had been one or two boyfriends, but they had not been serious, and her intuitive understanding of this had meant that the relationships had been brief. She saw no point, really, in persisting with a man who would not be with her in a year or two’s time. Why invest emotional energy in something that was not expected to last? In her view that led to disappointment and loss, and this could be avoided by simply not taking up with the man in the first place.

Then Matthew came into her life, and everything changed. It was at such a difficult time, too, very close to that traumatic incident when she had succumbed to her irritation over Olive’s mistreatment of Bertie—Olive had used her junior nurse’s kit to diagnose Bertie as suffering from leprosy—and had pinched Olive’s ear quite hard, something she had wanted to do for some time but which she had refrained from doing because to do so would be contrary to every principle of education and child care she had been taught. The fact that Olive richly deserved this pinch, and indeed might benefit from such a sharp reminder of moral cause and effect, was not a mitigating factor, and she had been obliged to resign from her position at the school. Matthew had been there to save her from the consequences of all this. While other boyfriends might have expressed regret over what she had done, and questioned its wisdom, Matthew sided with her completely and unequivocally, making it clear that he believed that the act of pinching Olive’s ear was a blow for pedagogic sanity.

“There are many children who would be improved by such a pinch,” he observed.

Elspeth thought about this. In normal circumstances she would follow the party line and say that one should never raise a hand to a child or indeed pinch any of its extremities, but mulling over Matthew’s pronouncement she came to the conclusion that she could think of quite a number of children who would benefit from a short, sharp pinch. Tofu, in particular, might be improved by a small amount of judiciously administered physical violence, even if only to stop him spitting at the other children. Perhaps if teachers spat at him he would get the message, but modern educational theory definitely frowned on teachers who spat at their pupils. That was the world in which we lived.

Domestic bliss seems in short supply at 44 Scotland Street. Over at the Pollock household, dad Stuart is harbouring a secret about a covert society and Bertie is feeling blue. He’s had enough of his neurotic mother and puts himself up for adoption on eBay. Will he go to the highest bidder or will he have to take matters into his own hands? The lovelorn Big Lou searches for true love on the internet, as Angus Lordie and Domenica get closer to getting hitched. But will they make it up the aisle?

Reviews

Excerpt

Tobermory’s tiny lungs, once filled with air, lost no time in expelling it in the form of a cry of protest. If birth—our first eviction—is a deeply unsettling trauma, and we are told by those who claim to remember it that it is, then this child was not going to let the experience go unremarked upon. Red with rage, he vented his anger as Matthew cradled him.

“Hush, Tobermory,” the new father crooned. “Hush, hush.”

On her pillow of pain, already exhausted by the effort of giving birth to two boys, Elspeth half-turned her head.

“Tobermory?”

“Just a working title,” said Matthew, above the sound of Tobermory’s screams. “It suits him, don’t you think?”

Elspeth nodded wearily. They had agreed in advance upon the name Rognvald, and had more or less decided on Angus and Fergus for the others, but Elspeth, being wary of having children who rhymed, was less enthusiastic about these last two names. Tobermory sounded rather attractive to her; she had been there once, on a boat from Oban, and had loved the brightly painted line of houses that followed the curve of the bay. Why were Scottish buildings grey, when they could be pink, blue, ochre? Moray Place, where they lived, could be transformed if only they would paint it that pink that one finds in houses in Suffolk, or the warm sienna of one or two buildings in East Lothian.

“Tobermory,” she muttered. “Yes, I rather like that.”

She returned to the task at hand, and a few minutes later gave birth to Fergus, who was markedly more silent than Tobermory, at whom he appeared to look reproachfully, as if censuring him for creating such a fuss.

The family of five was now complete. Matthew stayed in the hospital for a further hour, comforting Elspeth, who had become a bit weepy. Then, blowing a proud kiss to his three sons, he went back to the flat in Moray Place that the couple had moved into on the sale of their first matrimonial home in India Street. Once back, Matthew made his telephone calls—to his father, to Elspeth’s mother in Comrie, and to a list of more distant relatives whom he had promised to keep informed.

Then there were friends to contact, including Big Lou, who had been touchingly concerned over Elspeth’s condition during her pregnancy.

“You’re going to have to be really strong, Matthew,” she warned. “It’s not an easy thing for a lass to have triplets. You have to be there for her.”

You have to be there for her. Matthew had not expected that expression from Big Lou, whose turn of phrase reflected rural Angus rather than the psychobabble-speaking hills of California.

“I’ll be there for her, Lou,” he said, following her lead. “In whatever space she’s in, I’ll be there.”

“Good,” said Lou. “She’ll be fair trachled with three bairns. You too. You’ll be trachled, Matthew. It’s a sair fecht.”

“Aye,” said Matthew, lapsing into Scots. “I ken. I’ll hae my haunds fu.”

But now there was no word of caution from Big Lou.

“They’re all right, are they, Matthew?” she said over the telephone.

He assured her that they were, and she let out a whoop of delight. This show of spontaneous shared joy moved Matthew deeply. That another person should feel joy for him, should be proud when he felt proud, should share his heady, intoxicating elation, struck him as remarkable. Most people, he suspected, did not want others to be happy, not deep down. However we pretended otherwise, we resented the success of our friends; not that we did not want them to meet with success at all—it’s just that we did not want them to be markedly more successful than we were.

Matthew remembered reading somewhere that somebody had written—waspishly, but truly—every time a friend succeeds, I die a little. Gore Vidal: yes, he had said it. The problem, though, with witty people, thought Matthew, was working out whether they meant what they said.

It’s the wedding of the century as Angus Lordie finally ties the knot with Domenica Macdonald, but as the newlyweds depart on their honeymoon, Edinburgh is in disarray. Recovering from the trauma of being best man, Matthew is taken up by a Dane called Bo. Cyril eludes his dog-sitter and embarks on an adventure involving fox-holes and a cardinal. Narcissist Bruce meets his match in the form of a sinister doppelganger; Bertie, embarrassed again by his mother, yearns for freedom; and Big Lou goes viral.

Reviews

Excerpt

It rather surprised Domenica that she should suddenly think of poor Professor Santaluca after all these years. But it was quite understandable, really, that she should be contemplating the institution of marriage and its customs, given that she was herself about to get married—to Angus Lordie—and was now sitting in her flat in Scotland Street, attended by her friend, Big Lou, preparing for the moment—only three hours away—when she would walk through the door of St Mary’s Cathedral in Palmerston Place. Her entry would be to the accompaniment of “Sheep May Safely Graze” by Johann Sebastian Bach, this piece having been selected by Angus, who had a soft spot for Bach. Domenica had acceded to this provided that it would be her choice of music to be played as they left. That was Charles Marie Widor’s Toccata, from his Symphony No. 5, a triumphant piece of music if ever there was one.

“People will love it,” she said. “It’s such a statement.”

“Of what?” Angus had asked.

“Of the fact that the marriage has definitely taken place,” said Domenica. “It’s not a piece of music that admits of any ... how should I put it? ... uncertainty.”

“Maybe,” said Angus. “It’s the opposite of peelie-wersh, I suppose.”

Domenica was interested. As with many Scots expressions, the meaning of peelie-wersh was obvious, even to those who had never encountered the term before. “And which composers would be peelie-wersh?”

“Some of the minimalists. The ones who use two or three notes. The ones you have to strain to hear. Thin music. Widor is thickly textured.”

Summer blooms in Edinburgh and Bertie Pollock’s birthday appears on the horizon, but it’s not all cake and sunshine at 44 Scotland Street. Angus Lordie’s new wife has booked him into an institution that he must not call the loony bin and Bruce’s first encounter with hot wax brings more anguish than he bargained for.

Meanwhile Bertie’s birthday dreams of scout camp and a penknife may have to be replaced by a game of Royal Weddings and a gender-neutral doll. But fate, an amorous Bedouin, and the Dubai Tourist Authority conspire to transport Bertie’s mother Irene to a warmer place.

Reviews

Excerpt

Bertie Pollock (6) was the son of Irene Pollock (37) and Stuart Pollock (40), and older brother of Ulysses Colquhoun Pollock (1). Ulysses was also the son of Irene but possibly not of Stuart, the small boy bearing a remarkable resemblance to Bertie's psychotherapist, recently self-removed from Edinburgh to a university chair in Aberdeen. Stuart, too, had been promoted, having recently been moved up three rungs on the civil service ladder after incurring the gratitude of a government minister. This had happened after Stuart, in a moment of sheer frustration, had submitted the numbers from The Scotsman's Sudoku puzzle to the minister, representing them as likely North Sea oil production volumes. He had immediately felt guilty about this adolescent gesture—Homo ludens, playful man, might be appreciated in the arts but not in the civil service - and had he been able to retract the figures he would have done so. But it was too late; the minister was delighted with the encouraging projection, with the result that any confession by Stuart would have been a career-terminating event. So he remained silent, and was immensely relieved to discover later that the real figures, once unearthed, were so close to his Sudoku numbers as to make no difference. His conscience was saved by coincidence, but never again, he said to himself.

Irene had no interest in statistics and always adopted a glazed expression at any mention of the subject. “I can accept that what you do is very important, Stuart,” she said, in a pinched, rather pained tone, “but frankly it leaves me cold. No offence, of course.”

Her own interests were focused on psychology—she had a keen interest in the writings of Melanie Klein—and the raising of children. Bertie's education, in particular, was a matter of great concern to her, and she had already written an article for the journal Progressive Motherhood, in which she had set out the objectives of what she described as ‘the Bertie Project’.

“The emphasis,” she wrote, “must always be on the flourishing of the child's own personality. Yet this overriding goal is not incompatible with the provision of a programme of interest-enhancement in the child herself,” (Irene was not one to use the male pronoun when a feminine form existed). “In the case of Bertie, I constructed a broad and fulfilling programme of intellectual stimulation introducing him at a very early stage (four months) to the possibilities of theatre, music and the plastic arts. The inability of the very small infant to articulate a response to the theatre, for example, is not an indication of lack of appreciation—far from it, in fact. Bertie was at the age of four months taken to a performance by the Contemporary Theatre of Krakow at the Edinburgh Festival and reacted very positively to the rapid changes of light on the stage. There are many other examples. His response to Klee, for instance, was noticeable when he was barely three, and by the age of four he was quite capable of distinguishing Peploe from Matisse.”

Some of these claims had some truth to them. Bertie was, in fact, extremely talented, and had read way beyond what one might expect to find in a six-year-old. Most six-year-olds, if they can read at all, are restricted to the doings of Spot the Dog and other relatively unsubtle characters; Bertie, by contrast, had already consumed not only the complete works of Roald Dahl for children, but also half of Norman Lebrecht's book on Mahler and almost seventy pages of Miranda Carter's biography of the late Anthony Blunt. His choice of this reading, which was prodigious on any view, was dependent on what he happened to find lying about on his parents' bookshelves, and this was, of course, the reason why he had also dipped into several volumes of Melanie Klein and was acquainted too with a number of Freud's accounts of his famous cases, especially those of Little Hans and the Wolf Man.

Little Hans struck Bertie as being an entirely reasonable boy, who had just as little need of analysis as he himself had.

“I think Dr Freud shouldn't have worried about that boy Hans,” Bertie remarked to his mother, as they made their way one afternoon to the consulting rooms of Bertie's psychotherapist in Queen Street. “I don't think there was anything wrong with him, Mummy, I really don't.”

“That's a matter of opinion, Bertie,” answered Irene. “And actually it's Professor Freud, not Dr Freud.”

“Well,” said Bertie. “Professor Freud then. Why does he keep going on about ... ” He lowered his voice, and then became silent.

“About what, Bertie?” asked Irene. “What do you think Professor Freud goes on about?”

Bertie slowed his pace. He was looking down at the ground with studious intensity. “About bo ... ” he half-whispered. Modesty prevented his completing the sentence.

“About what, Bertie?” prompted Irene. “We mustn't mumble, carissimo. We must speak clearly so that others can understand what we have to say.”

Bertie looked anxiously about him. He decided to change the subject. “What about my birthday, Mummy?” he said.

Irene looked down at her son. “Yes, it's coming up very soon, Bertie. Next week, in fact. Are you excited?”

Bertie nodded. He had waited so long for this birthday—his seventh—that he found it difficult to believe that it was now about to arrive. It seemed to him that it had been years since the last one, and he had almost given up on the thought of turning seven, let alone eighteen, which he knew was the age at which one could leave one's mother. That was the real goal—a distant, impossibly exciting, shimmering objective. Freedom.

“Will I get any presents?” he asked.

Irene smiled. “Of course you will, Bertie.”

"I'd like a Swiss Army penknife," he half-whispered. “Or a fishing rod.”

Irene said nothing.

“Other boys have these things,” Bertie pleaded.

Irene pursed her lips. “Other boys? Do you mean Tofu?”

Bertie nodded miserably.

“Well the less said about him the better,” said Irene. She sighed. Why did men—and little boys too—have to hanker after weapons when they already had their ... She shook her head in exasperation. What was the point of all this effort if, after years of striving to protect Bertie from gender stereotypes, he came up with a request for a knife? It was a question of the number of chromosomes, she thought: therein lay the core of the problem.

The tenth book in the 44 Scotland Street series

The Revolving Door of Life: For young Bertie Pollock, life in Edinburgh has just gotten immeasurably better. The enforced absence of his endlessly pushy mother Irene—currently consciousness-raising in a Bedouin harem (don’t ask)—has manifold and immediate blessings: no psychotherapy, no Italian lessons, and no yoga classes. Bliss.

For Scotland Street’s grown-ups, life throws up some new dilemmas. Matthew makes a discovery that could make him even richer but also leaves him worried. Pat makes one that could make her poorer and her father miserable—unless that narcissist Bruce can help her out. And the Duke of Johannesburg, we discover, isn’t exactly who he says he is.

Reviews

Excerpt

Matthew had read somewhere—in one of those hoary lists with which newspapers and magazines fill their columns on quiet days—that moving house was one of the most stressful of life’s experiences—even if not quite as disturbing as being the victim of an armed robbery or being elected president, nemine contradicente, of an unstable South American republic. Matthew faced no such threats, of course, but he nevertheless found the prospect of leaving India Street for the sylvan surroundings of Nine Mile Burn extremely worrying. And it made no difference that Nine Mile Burn was, as the name suggested, only nine miles from the centre of Edinburgh.

“What really worries me,” he confessed to Elspeth, “is the whole business of selling India Street. What if nobody wants to buy this flat? What then?”

He looked at her with unconcealed anxiety: he could imagine what it was like not to be able to sell one’s house. He had recently been at a party at which somebody had whispered pityingly of another guest: “He can’t sell his flat, you know.” He had looked across the room at the poor unfortunate of whom the remark was made and had seen a hodden-doon, depressed figure, visibly bent under the burden of unshiftable equity. That, he decided, was how people who couldn’t sell their house looked—shadowy figures, wraiths, as dejected and without hope as the damned in Dante’s Inferno, haunted by the absence of offers for an unmoveable property. He had shuddered at the thought and reflected on his good fortune at not being in that position himself. Yet here he was deliberately courting it ...

Elspeth’s attitude was more sanguine. She had been unruffled by their previous moves—from India Street to Moray Place, and then back again to India Street. The prospect of another flit—a Scots word that implies an attempt to evade the clutches of creditors or suggests, misleadingly, that moving is an airy, inconsequential thing—did not seem to trouble her, and she had no concerns about the sale of the flat. “But of course somebody will want to buy it,” she reassured him. “Why wouldn’t they? It’s one of the nicest flats in the street. It’s got plenty of room and bags of light. Who wouldn’t want to live in the middle of the Edinburgh New Town?”

Matthew frowned. “The New Town isn’t for everybody,” he said. “Not everybody finds the Georgian aesthetic pleasing.” He paused as he tried to think of a single person he knew of whom this was true. “There are plenty of people these days who are suburban rather than urban. People who like to have ... ” He paused for thought. He knew nobody like this, but they had to exist. “Who like to have garages. Homo suburbiensis. Morningside man, who is a bit like Essex man but just a touch ... ”

“Superior?”

“You said it; I didn’t.”

Elspeth smiled. “You shouldn’t worry so much, Matt, darlingest. And so what if we don’t sell it? We can afford the other place anyway.”

Matthew winced. “If I dip into capital,” he said.

Elspeth shrugged. “But isn’t money for spending? And surely there’s enough there to be dipped into.”

Matthew knew that she was right; at the last valuation, his portfolio of shares in the astute care of the Adam Bank had shot up and he could have bought the new house several times over if necessary. But Matthew had been imbued by his father with exactly that sense of caution that had created the fund in the first place, and the idea of selling shares in any but the direst of emergencies was anathema to him.

In general, Elspeth did not look too closely at Matthew’s financial affairs. She had never been much interested in money, and very rarely spent any on anything but family essentials and the occasional outfit or pair of shoes. She was nonetheless aware of their good fortune and of the fact that thanks to the generosity of Matthew’s businessman father they were spared the financial anxieties that affected most people. Her capacity for moral imagination, though, was such that she could understand the distorting effect that poverty had on any life, and she had never been, nor ever would become, indifferent to the lot of those—perhaps a majority of the population of Scotland—who were left with relatively little disposable income after the payment of monthly bills. This attitude was shared by Matthew, with the result that they were tactful about their situation—and generous too, when generosity was required.

The farmhouse near Nine Mile Burn had not been cheap. Although it was far enough from Edinburgh to avoid the high prices of the capital, it was close enough to be more expensive than houses in West Linton, a village that lay only a few miles further down the road. Their house, which they had agreed to buy from no less a person than the Duke of Johannesburg, who lived at Single Malt House not far away, had been valued at seven hundred thousand pounds. For that they got six bedrooms in the main house—along with a study, a gun room (Matthew did not have a gun, of course), and a drawing room with a good view of both the Lammermuir and Moorfoot Hills to the south and east; a tractor shed, a byre, and six acres of ground.

The Duke had been pleased that Matthew was the purchaser; they had met on several occasions before, although the Duke seemed to have only the vaguest idea of who Matthew was. Matthew’s quiet demeanour, however, had been enough to endear him to the Duke.

“I must say,” the Duke had remarked to a friend, “it’s a great relief to have found somebody who’s not in the slightest bit shouty. You know what I mean? Those shouty people one meets these days—all very full of themselves and brash. We used to have very few of them in Scotland, you know; now they’re on the rise, it seems.”

The friend knew exactly what the Duke meant. “Nouveau riche,” he said. “They’re flashy—they throw their money around.”

The Duke nodded. “Whereas I’m nouveau pauvre. I’ve got barely a sou these days, you know—not that I ever had very much.”

“And you a duke,” said the friend. “Fancy that!”

“Well, a sort of duke,” conceded the Duke. “I’m not in any of the stud books, you know: Debrett’s and so on. Or I’m in one of them—just—but I gather it’s not a very reliable one. It was rather expensive to get in; you had to buy sixty copies, as I recall, and I think quite a number of people in it are a bit on the ropey side. In fact, all of them are, I believe.”

“People take you at your own evaluation, I’ve always thought,” said the friend. “Behave like a duke and they’ll swallow it.”

“True,” said the Duke. “But frankly, that’s a bit difficult for me, old man. I’m not quite sure what the form is when it comes to being a pukka duke.”

“Take a look at some of the people who are what they claim to be,” advised the friend. “Watch the way they stand; the way they walk. They’re very sure-footed, I’m told. And they look down at the ground a lot.”

“That’s because they own it,” said the Duke. “Doesn’t apply to me—or not very much. I’ve got fifty-eight acres in Midlothian and forty-one up in Lochaber, but most of it is pretty scrubby. Lots of broom and rhododenrons.”

The friend looked thoughtful. “No, you’re not quite the real thing, I suppose. And then there’s always the risk that the Lord Lyon will catch up with you.”

The mention of the Lord Lyon made the Duke blanch. This was the King of Arms, the official who supervised all matters of heraldry and succession in Scotland. He had extensive legal powers and could prosecute people for the unauthorised use of coats of arms and the like.

“Do you think Lyon would ever bother about me?” asked the Duke nervously.

His friend looked out of the window. “You never know,” he said. “But I shouldn’t like to be in your shoes if he did.”

It was not the sort of thing a friend should say—or at least not the sort of thing that a reassuring friend should say.

Our beloved cast of characters are back in The Bertie Project, as are the joys and trials of life at 44 Scotland Street.

Bertie’s mother, Irene, returns from the Middle East to discover that, in her absence, her son has been exposed to the worst of evils—television shows, ice cream parlors, and even unsanctioned art at the National Portrait Gallery. Her wrath descends on Bertie’s long-suffering father, Stuart. But Stuart has found a reason to spend more time outside of the house and seems to have a new spring in his step. What does this mean for the residents of 44 Scotland Street?

The winds of change have come to the others as well. Angus undergoes a spiritual transformation after falling victim to an unexpected defenestration. Bruce has fallen in a rather different sense for a young woman who is determined to share with him her enthusiasm for extreme sports. Matthew and Elspeth have a falling out with their triplets’ au pair, while Big Lou continues to fall in love with her new role as a mother. And as Irene resumes work on what she calls her Bertie Project, reinstating Bertie’s Italian lessons, yoga classes, and psychotherapy, Bertie begins to hatch a project of his own—one that promises freedom.

Reviews

Reviews

To everything there is a season and a time for every purpose; it is summer in Scotland Street (as it always is) and for the habitués of Edinburgh’s favourite street some extraordinary adventures lie in waiting.

For the impossibly vain Bruce Anderson – he of the clove-scented hair gel – it may finally be time to settle down, and surely it can only be a question of picking the lucky winner from the hordes of his admirers. The Duke of Johannesburg is keen to take his flight of fancy, a microlite seaplane, from the drawing board to the skies. Big Lou is delighted to discover that her young foster son has a surprising gift for dance but she is faced with big decisions to make on his and her futures. And with Irene now away to pursue her research in Aberdeen, her husband, Stuart, and infinitely long-suffering son, Bertie, are free to play. Stuart rekindles an old friendship over peppermint tea whilst Bertie and his friend Ranald Braveheart Macpherson get more they bargained for from their trip to the circus. And that’s just the start …

Once more we catch up with the delightful goings-on in the fictitious 44 Scotland Street from Alexander McCall Smith … Bertie and the gang return for another series of heart-warming, laugh-out-loud escapades in Edinburgh’s favourite street. Told with all of McCall Smith’s customary charm and deftness, this will be your perfect summer read.

Reviews

To everything there is a season and a time for every purpose; it is summer in Scotland Street (as it always is) and for the habitués of Edinburgh’s favourite street some extraordinary adventures lie in waiting. Join Bertie, Irene, Stuart and all the rest for another 44 Scotland Street tale.

Take a few minutes to relax and savour the affairs of the world in microcosm, teeming with life’s loves and challenges. Little dramas writ large by the master chronicler of modern life and manners in the latest book in the 44 Scotland Street series, now the world’s longest-running serial novel.

A 44 Scotland Street Novel.

Life for Bertie seems to be moving at a pace that is rather out of his control. Upstairs, at 44 Scotland Street, his father Stuart is powerless to stop over-bearing Irene and her determination that Bertie will travel to deepest, coldest Aberdeen on a three-month sojourn. Can his friend Ranald Braveheart Macpherson save the day? And can the boys execute a great escape? Meanwhile, further up in the New Town, Bruce Anderson’s property development plans are thwarted by a sudden crisis of conscience that leads to a shocking revelation. And, in Big Lou’s cafe, it seems that love might blossom at last.

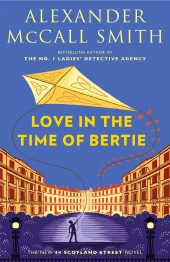

Warm hearted, humorous and always wonderfully wise, Love in the Time of Bertie offers philosophical insight as well as sartorial elegance. There are tribulations as well as celebrations in this the next instalment in the 44 Scotland Street series.

The 44 Scotland Street door-knocker as it appears in The Scotsman newspaper

Reviews